2 Background & Concept

This chapter introduces the history of the plans to set up a European music observatory and a decentralised approach, the creation of CEEMID–a background of the Open Music Europe project and an important building block established in the EMO feasibility study.

The key lesson of the CEEMID project was that, unlike observatories that started in the late 20th and early 21st century, modern data ecosystems grow faster and can incorporate big data sources if they are decentralised. Therefore, we conceptualise the Open Music Observatory as a data (sharing) space, a novel technical and legal innovation of the European Union. (See Section 2.2.) We place an emphasis on compliance with the European Interoperability Framework and embracing the open collaboration method, open source software and open data as fundamental building blocks.

At last, we review a few observatories (Section 2.5), including the ones that were reviewed in the EMO feasibility study to see what services they offer in 2024, and how our service structure compares to theirs.

2.1 History of the Music Observatory

In late 2015, the European Commission started a dialogue with representatives from the music sector1 in Europe to identify key challenges and possible ways to tackle them, including EU support. Music Moves Europe has become the framework for these discussions and, more broadly, for EU initiatives and actions to promote the diversity and competitiveness of Europe’s music sector regarding policy and funding. As part of the 2018 Preparatory Action Music Moves Europe: Boosting European Music Diversity and Talent the EU commissioned the creation of The feasibility study for the establishment of a European Music Observatory (European Commission et al. 2020) (in short: EMO Feasibility Study).

In 2020, Feasibility Study for the Establishment of a European Music Observatory : Final Report enumerates 45 data gaps where music stakeholders and policymakers are lacking information to develop business and policy actions to increase the competitiveness, value-added and job creation capacity, and diversity of the European music ecosystem. It also called out the fact that “data collection in Eastern and Southern Europe is lagging in comparison to other European Member States in Northern and Western Europe”, and highlighted the importance of the former CEEMID project (a predecessor of Open Music Europe) as a possible data source for a new European Music Observatory.

“Data collection in Eastern and Southern Europe is lagging in comparison to other European Member States in Northern and Western Europe, with the respective music sectors in most Eastern Europe countries and smaller EU Member States not fully developed, and lacking the tools and processes to gather economic, cultural and social data on the music sector. These data conditions and the problems they present for effective management and policy development are the fundamental reasons for supporting the creation of a European Music Observatory. In particular, robust and meaningful comparative data collected at a regular basis are essential when it comes to assessing the need for interventions at the EU level to address gaps in the market and enhance the efficiencies and global competitiveness of the sector”. (European Commission et al. 2020, p9–10)

It also mentioned the work of CEEMID, a bottom-up initiative originally started by three collective management societies (Artisjus et al. 2014). Our proposal wants to put the former CEEMID, currently named Digital Music Observatory, a more solid scientific and methodological foundation to make it more user-friendly and to exploit state-of-art statistical, data science and computer science methods to provide more comprehensive, timely, and accurate services for the European music sector.

The former CEEMID (originally: Central & Eastern European Music Industry Databases) collaboration offered data and a more modern, decentralised organisational alternative to the creation of the observatory. CEEMID was organised in 2014 according to the principles of a so-called data (sharing) space, which by 2024 would be a cornerstone of the European data strategy and a recognised organisational and legal vehicle to create interoperable digital services in the EU. Initiated by four organisations (out of which three are members of the Open Music Europe consortium) and eventually joined by more than 60 stakeholders in 12 European countries to fill in some of these gaps with a) voluntary data integration among partners, b) open data re-processing c) co-financed data collection (Antal 2020).

Three former CEEMID partners took a subjective view of the data gaps identified by the feasibility study and, together with further academic and industry partners, applied for a highly competitive Horizon Europe Research and Innovation Action Grant. After winning the grant, we formed the Open Music Europe Consortium and collected the data.

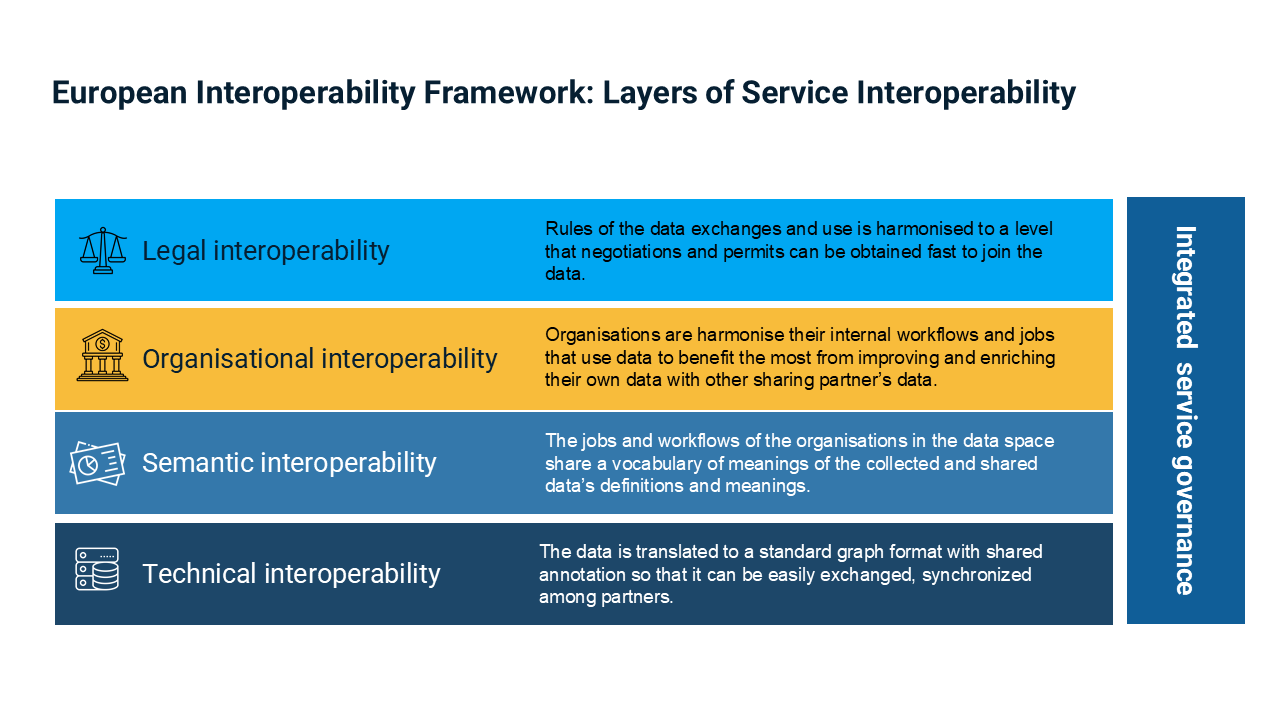

Since the publication of the EMO feasibility study, the fruits of the European Interoperability Framework applied to digital public services and the European Open Science Cloud, or the planned European Collaborative Cloud for Cultural Heritage, provide solutions that strongly favour a decentralised information model for a new observatory. We imagine a future European Music Observatory that is not a specialised knowledge institution or a library, archive, museum, or statistical agency. Instead, applying the European Interoperability Framework should be able to consolidate knowledge from all such knowledge and statistical institutions and find ways to combine data from private enterprises and data collection programs to fill the information gaps of the European music sector stakeholders.

[…]Potential stakeholders for the purposes of this project: Industry: those organisations and agents who are linked to the economy of the music sector, representing commercial, for profit interests only. Example: commercial organisations and companies which are involved in the business of music making including organisations which represent those involved in income-generation from the performance, recording, distribution and creation of music. Civic: those organisations and agents who are linked to the policies affecting the music sector. Civic should be organisations with a general interest mandate, professional associations receiving public funding, and/or including public entities in their membership. Example: political and non-political policymakers whose decisions impact on performance, recording, distribution and creation of music including NGOs and funding distributors. Public: those organisations and agents who are linked to the wider culture of music making and consumption. Example: organisations representing consumers, voluntary and third sector, education and training sector with an interest in the performance, recording, distribution and creation of music. (European Commission et al. 2020, p30)

2.2 Open Music Dataspace

Our system definition for the Open Music Observatory, we follow the data (sharing) space model that has been developed in recent years and has become a foundational concept of the digital aspect of the strategic policy agenda of triple transition to a more sustainable, digital and just European society.

The data (sharing) space concept has been evolving in recent years. There are several complementary and consistent definitions available that place more or less emphasis on the business processes, the technical processes, or the domain-specific problems. We have considered the following definitions when we arrived to our Open Music Dataspace definition above.

In Dataspaces: Fundamentals, Principles, and Technique : (Curry 2020) defines a dataspace as “an emerging approach to data management which recognises that in large-scale integration scenarios, involving thousands of data sources, it is difficult and expensive to obtain an upfront unifying schema across all sources. Data is integrated on an ‘as-needed’ basis, with the labour-intensive aspects of data integration postponed until they are required. Dataspaces reduce the initial effort required to set up data integration by relying on automatic matching and mapping generation techniques.” This definition stresses prioritising an ongoing, dynamic data curation process instead of the less realistic “one-solution-fits-all” approach applied earlier.

Extending this definition in the Design Principles for Data Spaces (Position paper) adds the idea of federation: “From a technical perspective, a data space can be seen as a data integration concept which does not require common database schemas and physical data integration, but is rather based on distributed data stores and integration on an”as needed” basis on a semantic level. Abstracted from this technical definition, a data space can be defined as a federated data ecosystem within a certain application domain and based on shared policies and rules.” (Nagel and Lycklama 2021, p7). The ability to start building similarly organised data-sharing spaces with similar enough principles to federate them into a larger union of data space is a critically important idea in our system and governance design.

`

The position paper of the European Broadcasting Union and Gaia-X Dataspace for Cultural and Creative Industries highlights the aspect that a “data space is an ecosystem of exchange, processing, sharing and provision of data between trusted partners, for a fee or not. It is not about copying or repatriating data centrally, but about ensuring that each data holder has full control over the conditions (e.g., who, when, and under what condition) of access to their data.” (EBU and Gaia-X 2022, p16) Not only because this position paper deals with cultural and creative industries data but also because it stresses the need to provide protocols for reconciliation between open and public and private data sources, we took special attention to this position paper.

2.2.1 European Interoperability Framework

data interoperability: the ability of two or more systems or applications to exchange information and to mutually use the information that has been exchanged. [SOURCE:ISO/IEC 19941:2017]

data portability: the ability to easily transfer data from one system to another without being required to re-enter data.

2.2.2 Embrace open

According to the study published by the European Commission on the impact of open-source software (OSS) and open-source hardware (OSH) on the European economy, conducted by Fraunhofer ISI and Open Forum Europe on 6 September 2021, open-source software contributed between €65 to €95 billion to the European Union’s GDP. It promises significant growth opportunities for the region’s digital economy. The 2020 report on the Economic Value of Open Data estimated the value of open data available in the European economy at €184 billion and is forecasted to reach between €199.51 and €334.21 billion in 2025. To unlock this potential, the study makes similar but less specific recommendations as the OSS/OSH study described above2.

2.2.3 Open Music Dataspace

Open Music Dataspace: as the data management of the Open Music Observatory, it recognises that in a large-scale integration of music sector data involving potentially thousands of data sources, it is impossible to create a unifying schema across all sources. It is an exchange, processing, sharing and provision of data between trusted partners, for a fee or not. It is not necessarily copying or repatriating data centrally but ensures that each data holder has complete control over the conditions (e.g., who, when, and under what conditions) of access to their data. We create this data-sharing space view that certain national, genre-specific or other interest groups may want to apply a deeper level of integration and exchange and, through federation, extend the part of their data sharing to the entire Open Music Observatory. The application of automatic matching and mapping generation techniques, widely used conceptual models, and the concepts of the European Interoperability Framework allow the Observatory Stakeholder Network to integrate data on an ‘as-needed’ or as-permitted basis, keeping the data ready for integration whenever the data owners agree on such a need.

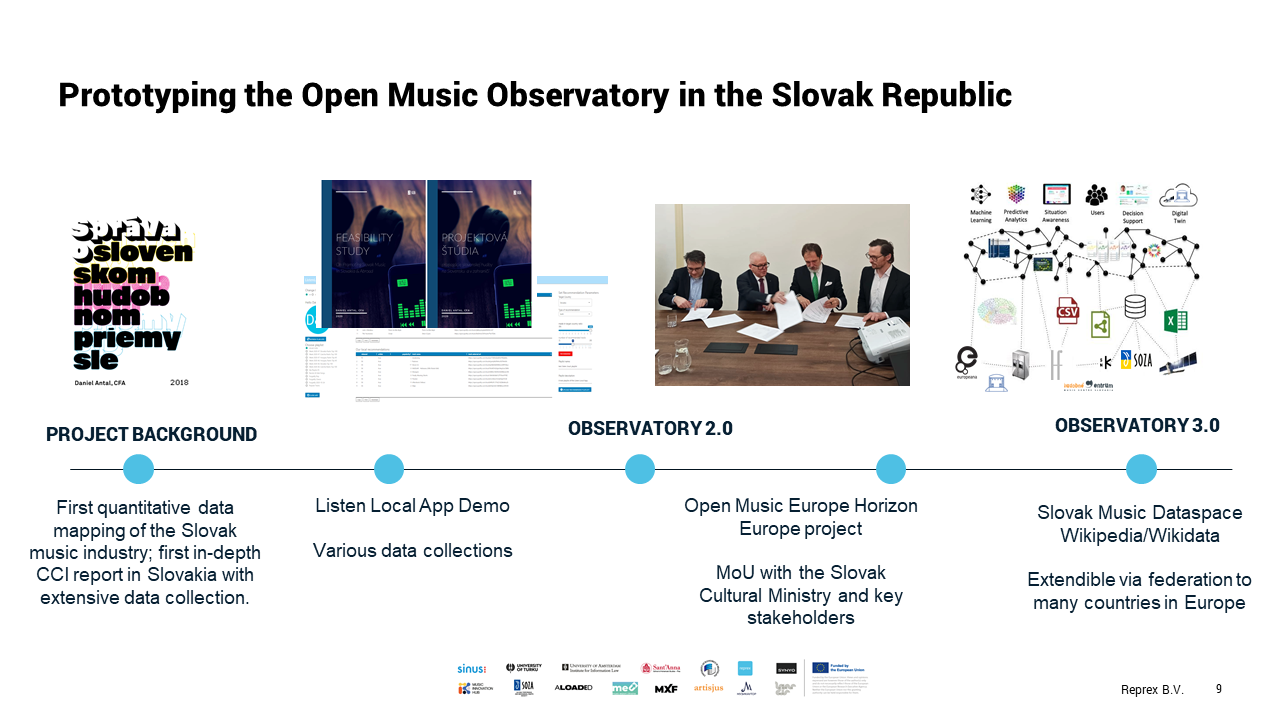

2.3 Prototyping in Slovakia

Because a significant part of the Open Music Europe background was developed or tested in Slovakia, we decided to start prototyping the Open Music Observatory in this country.

Slovak Music Dataspace: a dataspace organised by SOZA, Reprex, and Hudobné centrum to share and exchange data on music related to the Slovak Republic. It provides a secure data exchange supported by trustworthy AI to harmonise and exchange data among representative Slovak music organisations and to create the public Slovak Music Register and the Slovak Comprehensive Music Database.

In a significant stride towards our shared vision, we signed a Memorandum of Understanding in March 2023 (Ministerstvo kultúry SR and Open Music Europe 2023). This strategic alliance includes key stakeholders, such as the Ministry of Culture, and is aimed at establishing a robust public-private partnership. This partnership will play a pivotal role in sharing, exchanging, and improving data related to music in the Slovak Republic, thereby fostering a vibrant music ecosystem.

Slovakia has a relatively advanced statistical system: one of the few EU member states with a satellite accounting system for the cultural and creative industry to augment the country’s national accounts. The methodological work related to coordinating governmental and privately held data is the subject of other tasks; in making the Open Music Observatory, we only provide the infrastructure and the dissemination of knowledge for replication.

Because we apply GSIM, DDI and SDMX, like the Slovak statistical system, our solutions are replicable in an EU/EEA member state or candidate country that has sufficiently aligned its statistical practices with the European Statistical System.

2.4 Stakeholder presentations

We presented our work and ideas on the International Association of Music Centres (IAMIC) general assembly and conference in November 2024 3.

We presented our paper and poster on the International Association of Music Libraries, Archives and Documentation Centres 4.

2.5 Other observatories

The EMO feasibility study presented several observatories to compare their services and organisational models. As more than five years have passed since the data collection for that study, we highlight here some of the considered comparators and add a few more.

2.5.1 Feasibility study

The Feasibility study directly mentions some observatories as possible good practice to be used wile working on the European Music Observatory.

Chapter 1.5. is about the European Audiovisual Observatory (EAO) which has a great impact “on creating a consensual mapping environment for the audiovisual sector” (p. 25) and would be a good example to model the OMO after.

The European Market Observatory for Fisheries and Aquaculture Products (EUMOFA) is known to operate under a service contract, which is awarded through a tender - a potential way the “to integrate the European Music Observatory setup directly within the competent services of the Commission” (p. 47)

The basis of the Directorate-General for Agriculture and Rural Development (DG-AGRI) market observatories can be used to establish the OMO, but the downside is the lack of legal obligation for data transparency in the music sector, which is present in agriculture, thus making it difficult to replicate the legal basis. (p. 48)

The European Observatory on Infringements of Intellectual Property Rights (EUIPO) along with EAO is mentioned as possible partners to work with OMO and the tasks of OMO could be potentially integrated into within these partners. (p. 48) The details of this integration is discussed in chapter 3.8.6 (p. 89-91).

2.5.2 Milk market observatory

The aim of the EU milk market observatory is to provide the EU dairy sector with more transparency by means of disseminating market data and short-term analysis in a timely manner.

- Publications: regular, in PDF document.

- Statistical data access: Agri-food data portal

- API: Agri-food data API

- EU Open Data portal: yes, via Directorate-General for Agriculture and Rural Development

- Newsletter:

- License: The Commission’s reuse policy is implemented by the Commission Decision of 12 December 2011 on the reuse of Commission documents. Unless otherwise indicated (e.g. in individual copyright notices), content owned by the EU on this website is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) licence. This means that reuse is allowed, provided appropriate credit is given and changes are indicated.

2.5.3 European Audiovisual Observatory (EAO)

- Link: https://www.obs.coe.int/en/web/observatoire/

- Publications: regular, in PDF and xlsx document

- Statistical data access:

- API: No.

- EU Open Data portal: ?

2.5.4 European Observatory on Infringements of Intellectual Property Rights (EUIPO)

“The European Observatory on Infringements of Intellectual Property Rights is a network of experts and specialist stakeholders that brings together representatives from EU bodies, authorities in EU countries, businesses and civil society. The aim of the observatory is to improve the fight against counterfeiting and piracy by sharing information and best practice, raising public awareness, strengthening cooperation, and developing better tools.” [https://single-market-economy.ec.europa.eu/industry/strategy/intellectual-property/enforcement-intellectual-property-rights/european-observatory-infringements-intellectual-property-rights_en]

The legal mandate of managing the observatory is in the Regulation No 386/2012.

Publications: regular, in PDF document

Statistical data access: Several, under “Services” Menu

API:The observatory does not appear to offer datasets.

EU Open Data portal: via Directorate-General for Communications Networks, Content and Technology some publication and datasets of the EUIPO are available.

License: The observatory does not appear to offer datasets.

2.5.5 European Market Observatory for Fisheries and Aquaculture Products (EUMOFA)

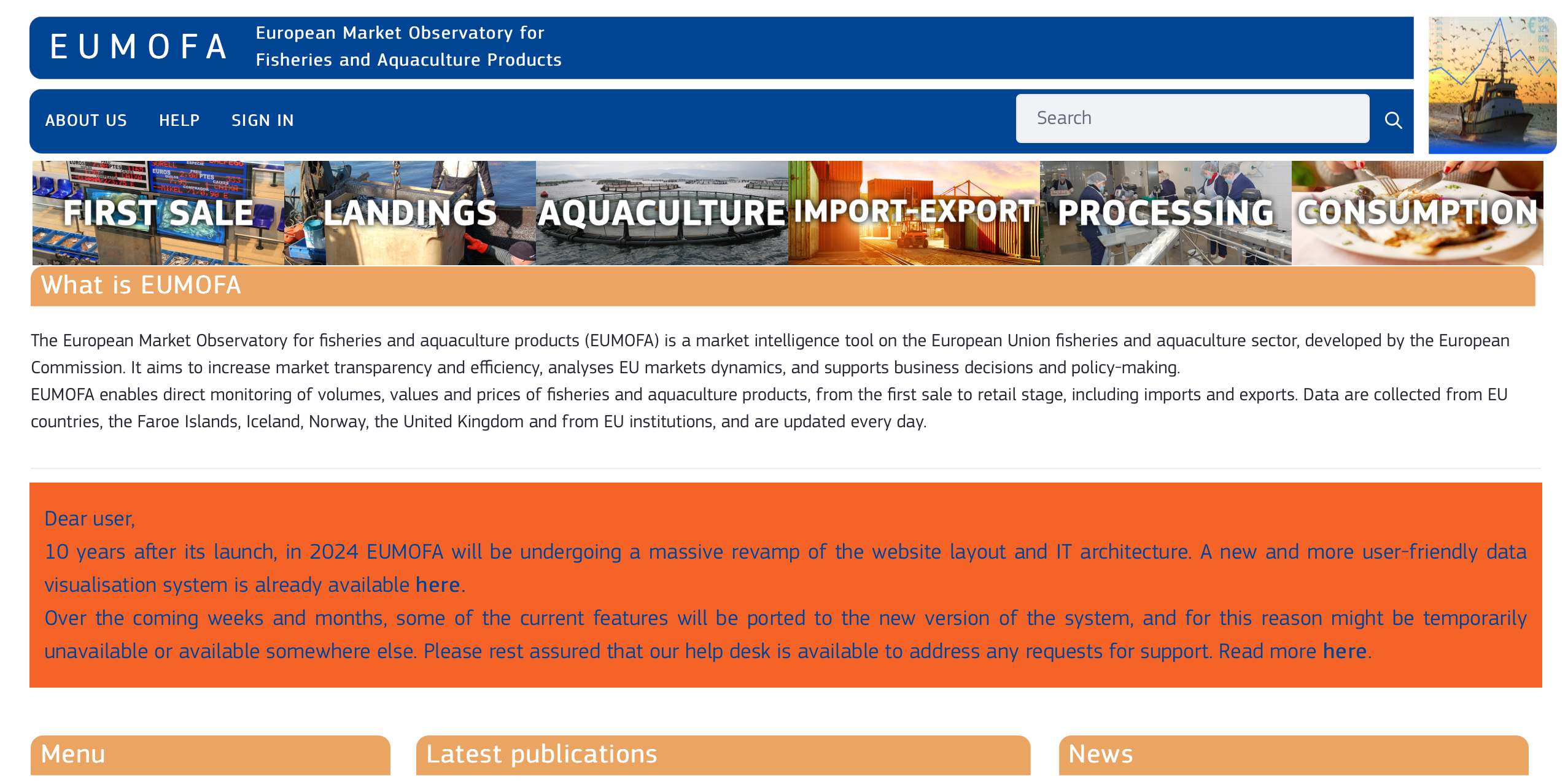

The European Market Observatory for fisheries and aquaculture products (EUMOFA) is a market intelligence tool on the European Union fisheries and aquaculture sector, developed by the European Commission. It aims to increase market transparency and efficiency, analyses EU markets dynamics, and supports business decisions and policy-making.

EUMOFA enables direct monitoring of volumes, values and prices of fisheries and aquaculture products, from the first sale to retail stage, including imports and exports. Data are collected from EU countries, the Faroe Islands, Iceland, Norway, the United Kingdom and from EU institutions, and are updated every day.

Link: https://eumofa.eu

Publications: regular, in PDF documents.

Statistical data access: EUMOFA DATA

API: via the Directorate-General for Maritime Affairs and Fisheries API or via EU Open Data portal: yes, via Directorate-General for Maritime Affairs and Fisheries

License: European Commission Reuse and Copyright Notice (Decision of 12 December 2011).

See European Commission (2021a) about the policy-making process and objectives.↩︎

See The Impact of Open Source Software and Hardware on Technological Independence, Competitiveness and Innovation in the EU Economy (European Commission et al. 2021)and Economic Value of Open Data (Huyer and van Knippenberg 2020).↩︎

Poster: (Antal 2024).↩︎

SKCMDB: Interoperability of Music Libraries and Archives with Public and Private Music Services and poster: (Antal 2024).↩︎

](https://agriculture.ec.europa.eu/sites/default/files/styles/oe_theme_medium_no_crop/public/2024-04/mmo-dairy_600x400.png)